PathSim is a flexible block-based time-domain system simulation framework in Python with automatic differentiation capabilities and an event handling mechanism! It provides a variety of classes that enable modeling and simulating complex interconnected dynamical systems through Python scripting.

All of that with minimal dependencies, only numpy, scipy and matplotlib (and dill if you want to use serialization)!

Key Features:

- Dynamic system modification at simulation runtime, i.e. triggered through events

- Automatic block- and system-level linearization at runtime

- Wide range of numerical integrators (implicit, explicit, high order, adaptive), able to handle stiff systems

- Modular and hierarchical modeling with (nested) subsystems

- Event handling system to detect and resolve discrete events (zero-crossing detection)

- Automatic differentiation for end-to-end differentiable simulations

- Extensibility by subclassing the base

Blockclass and implementing just a handful of methods

For the full documentation, tutorials and API-reference visit Read the Docs!

The source code can be found in the GitHub repository and is fully open source under MIT license. Consider starring PathSim to support its development.

The latest release version of PathSim is available on PyPi and installable via pip:

pip install pathsimThere are lots of examples of dynamical system simulations in the GitHub repository that showcase PathSim's capabilities.

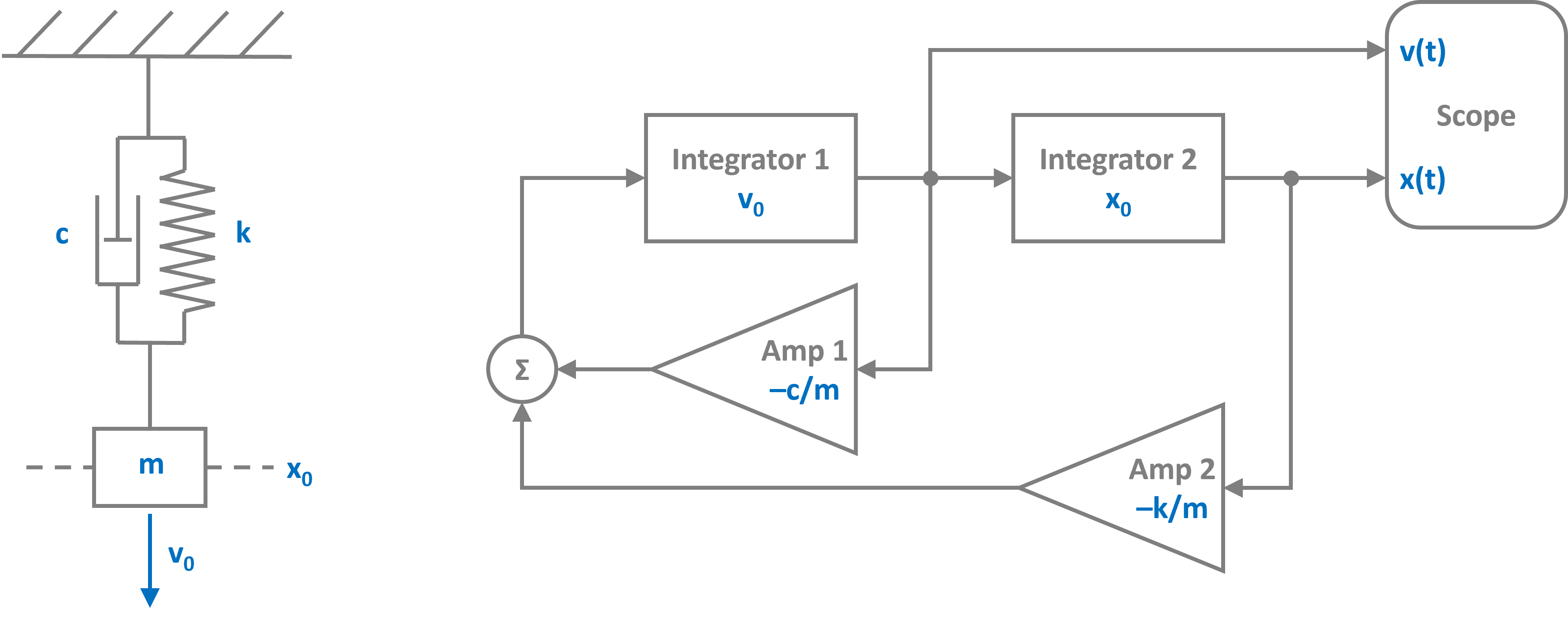

But first, lets have a look at how we can simulate the harmonic oscillator (a spring mass damper 2nd order system) using PathSim. The system and its corresponding equivalent block diagram are shown in the figure below:

The equation of motion that defines the harmonic oscillator it is give by

where

The topology of the block diagram above can be directly defined as blocks and connections in the PathSim framework. First we initialize the blocks needed to represent the dynamical systems with their respective arguments such as initial conditions and gain values, then the blocks are connected using Connection objects, forming two feedback loops.

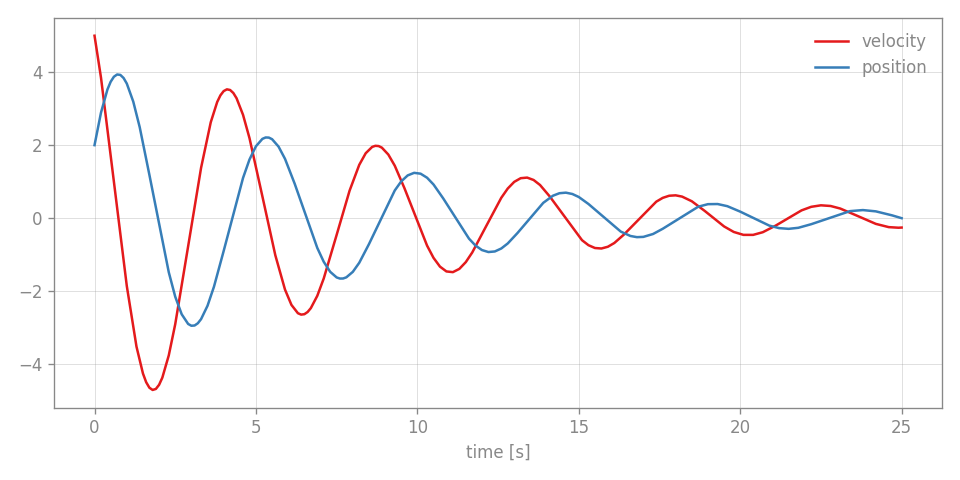

The Simulation instance manages the blocks and connections and advances the system in time with the timestep (dt). The log flag for logging the simulation progress is also set. Finally, we run the simulation for some number of seconds and plot the results using the plot() method of the scope block.

from pathsim import Simulation, Connection

#import the blocks we need for the harmonic oscillator

from pathsim.blocks import Integrator, Amplifier, Adder, Scope

#initial position and velocity

x0, v0 = 2, 5

#parameters (mass, damping, spring constant)

m, c, k = 0.8, 0.2, 1.5

#define the blocks

I1 = Integrator(v0) # integrator for velocity

I2 = Integrator(x0) # integrator for position

A1 = Amplifier(-c/m)

A2 = Amplifier(-k/m)

P1 = Adder()

Sc = Scope(labels=["v(t)", "x(t)"])

blocks = [I1, I2, A1, A2, P1, Sc]

#define the connections between the blocks

connections = [

Connection(I1, I2, A1, Sc), # one to many connection

Connection(I2, A2, Sc[1]),

Connection(A1, P1), # default connection to port 0

Connection(A2, P1[1]), # specific connection to port 1

Connection(P1, I1)

]

#create a simulation instance from the blocks and connections

Sim = Simulation(blocks, connections, dt=0.05)

#run the simulation for 30 seconds

Sim.run(duration=30.0)

#plot the results directly from the scope

Sc.plot()

#read the results from the scope for further processing

time, data = Sc.read()PathSim implements a large variety of implicit integrators such as diagonally implicit runge-kutta (DIRK2, ESDIRK43, etc.) and multistep (BDF2, GEAR52A, etc.) methods. This enables the simulation of very stiff systems where the timestep is limited by stability and not accuracy of the method.

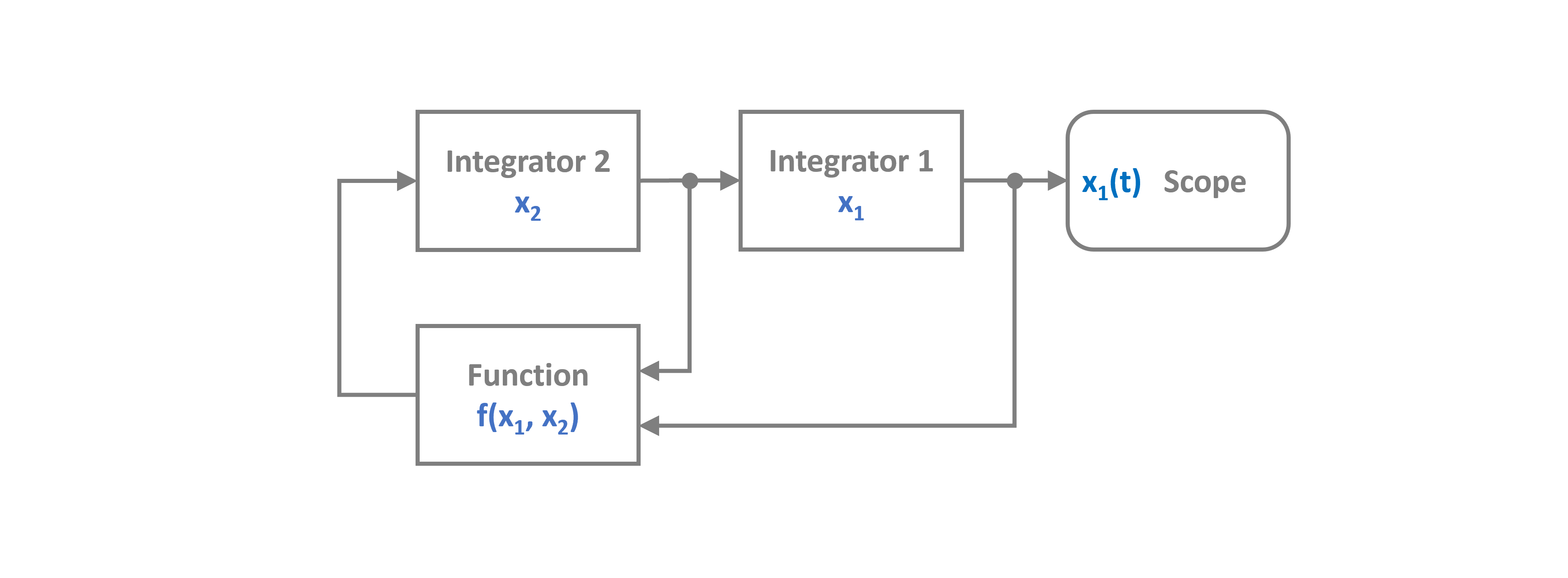

A common example for a stiff system is the Van der Pol oscillator where the parameter

The Van der Pol ODE can be translated into a block diagram like the one below, where the two states are handled by two distinct integrators.

Lets translate it to PathSim using two Integrator blocks and a Function block. The parameter is set to

from pathsim import Simulation, Connection

from pathsim.blocks import Integrator, Scope, Function

#implicit adaptive timestep solver

from pathsim.solvers import ESDIRK54

#initial conditions

x1, x2 = 2, 0

#van der Pol parameter (1000 is very stiff)

mu = 1000

#blocks that define the system

Sc = Scope(labels=["$x_1(t)$"])

I1 = Integrator(x1)

I2 = Integrator(x2)

Fn = Function(lambda x1, x2: mu*(1 - x1**2)*x2 - x1)

blocks = [I1, I2, Fn, Sc]

#the connections between the blocks

connections = [

Connection(I2, I1, Fn[1]),

Connection(I1, Fn, Sc),

Connection(Fn, I2)

]

#initialize simulation with the blocks, connections, timestep and logging enabled

Sim = Simulation(

blocks,

connections,

dt=0.05,

Solver=ESDIRK54,

tolerance_lte_abs=1e-5,

tolerance_lte_rel=1e-3

)

#run simulation for some number of seconds

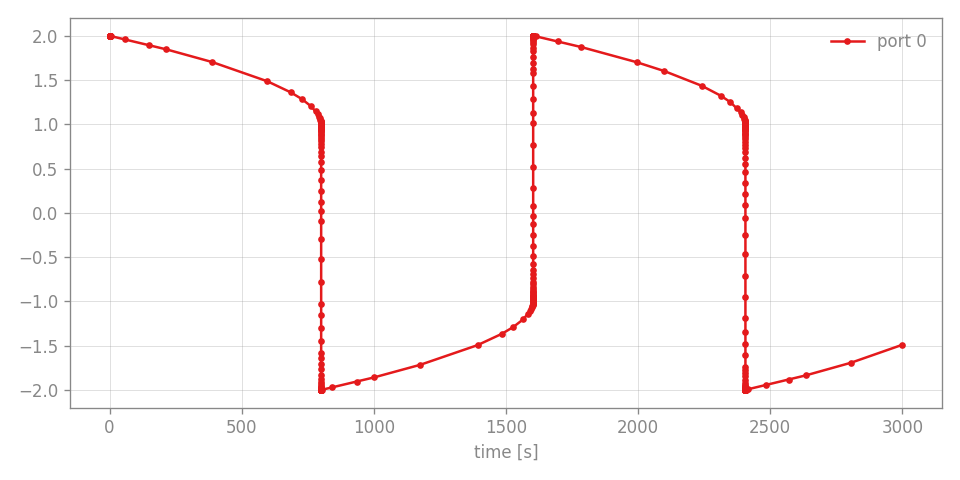

Sim.run(3*mu)

#plot the results directly (steps highlighted)

Sc.plot(".-")PathSim also includes a fully fledged automatic differentiation framework based on a dual number system with overloaded operators and numpy ufunc integration. This makes the system simulation fully differentiable end-to-end with respect to a predefined set of parameters. Works with all integrators, adaptive, fixed, implicit, explicit.

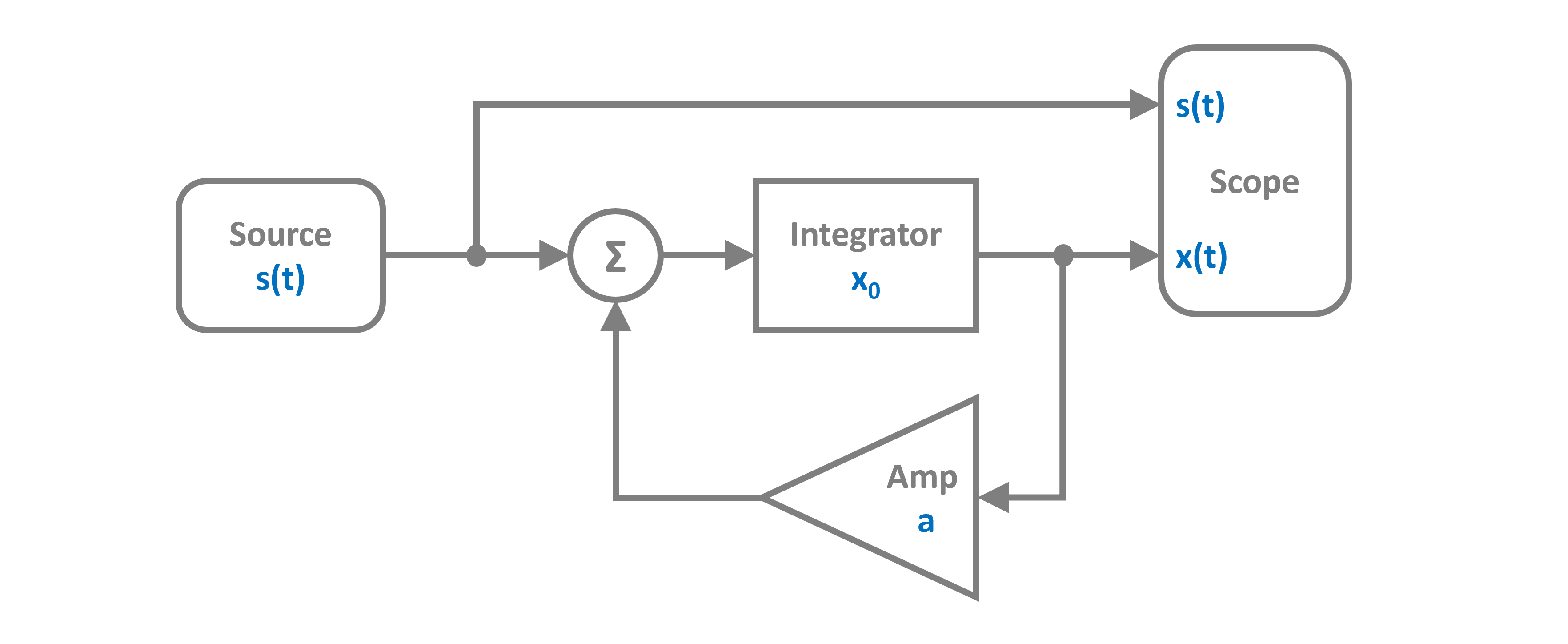

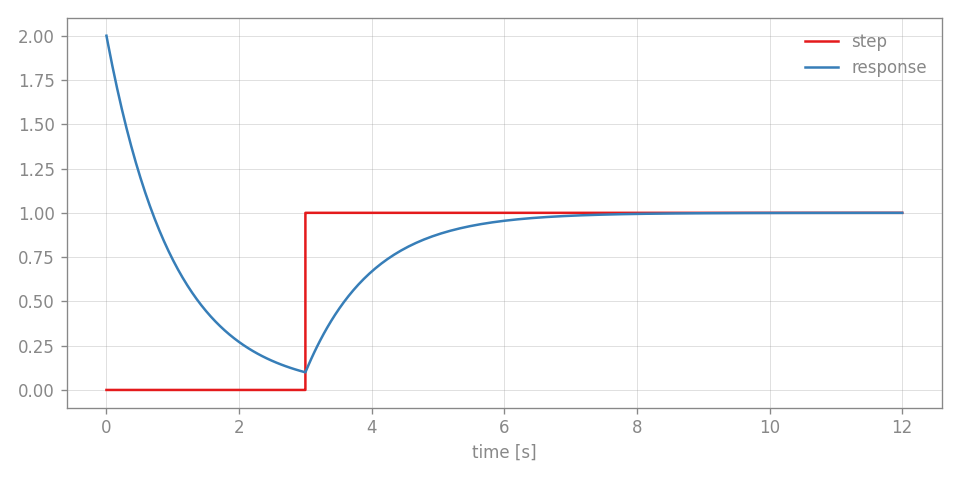

To demonstrate this lets consider the following linear feedback system and perform a sensitivity analysis on it with respect to some system parameters.

The source term is a scaled unit step function (scaled by

from pathsim import Simulation, Connection

from pathsim.blocks import Source, Integrator, Amplifier, Adder, Scope

#AD module

from pathsim.optim import Value, der

#values for derivative propagation / parameters for sensitivity analysis

a = Value(-1)

b = Value(1)

x0 = Value(2)

#simulation timestep

dt = 0.01

#step function

tau = 3

def s(t):

return b*int(t>tau)

#blocks that define the system

Src = Source(s)

Int = Integrator(x0)

Amp = Amplifier(a)

Add = Adder()

Sco = Scope(labels=["step", "response"])

blocks = [Src, Int, Amp, Add, Sco]

#the connections between the blocks

connections = [

Connection(Src, Add[0], Sco[0]),

Connection(Amp, Add[1]),

Connection(Add, Int),

Connection(Int, Amp, Sco[1])

]

#initialize simulation with the blocks, connections, timestep

Sim = Simulation(blocks, connections, dt=dt)

#run the simulation for some time

Sim.run(4*tau)

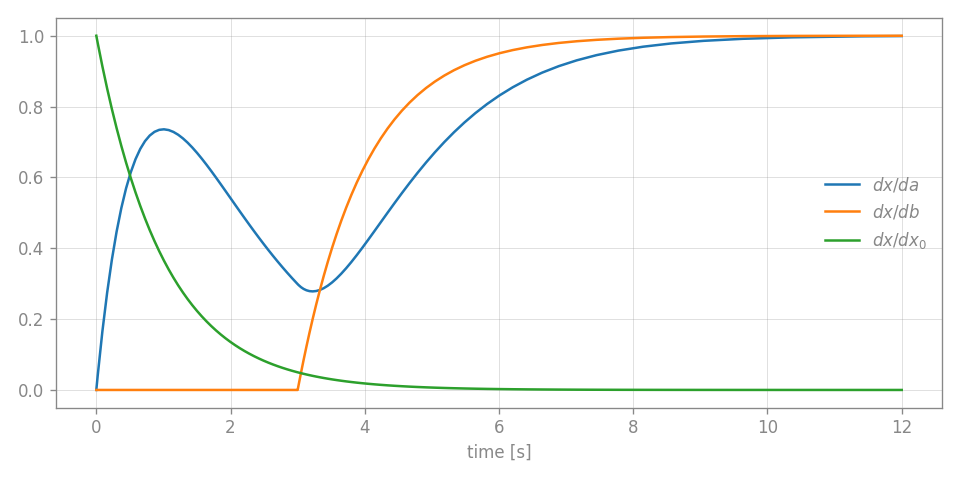

Sco.plot()Now the recorded time series data is of type Value and we can evaluate the automatically computed partial derivatives at each timestep. For example the response, differentiated with respect to the linear feedback parameter der(data, a).

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#read data from the scope

time, [step, data] = Sco.read()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=1, tight_layout=True, figsize=(8, 4), dpi=120)

#evaluate and plot partial derivatives

ax.plot(time, der(data, a), label=r"$\partial x / \partial a$")

ax.plot(time, der(data, x0), label=r"$\partial x / \partial x_0$")

ax.plot(time, der(data, b), label=r"$\partial x / \partial b$")

ax.set_xlabel("time [s]")

ax.grid(True)

ax.legend(fancybox=False)PathSim has an event handling system that monitors the simulation state and can find and locate discrete events by evaluating an event function and trigger callbacks or state transformations. Multiple event types are supported such as ZeroCrossing or Schedule.

This enables the simulation of hybrid continuous time systems with discrete events.

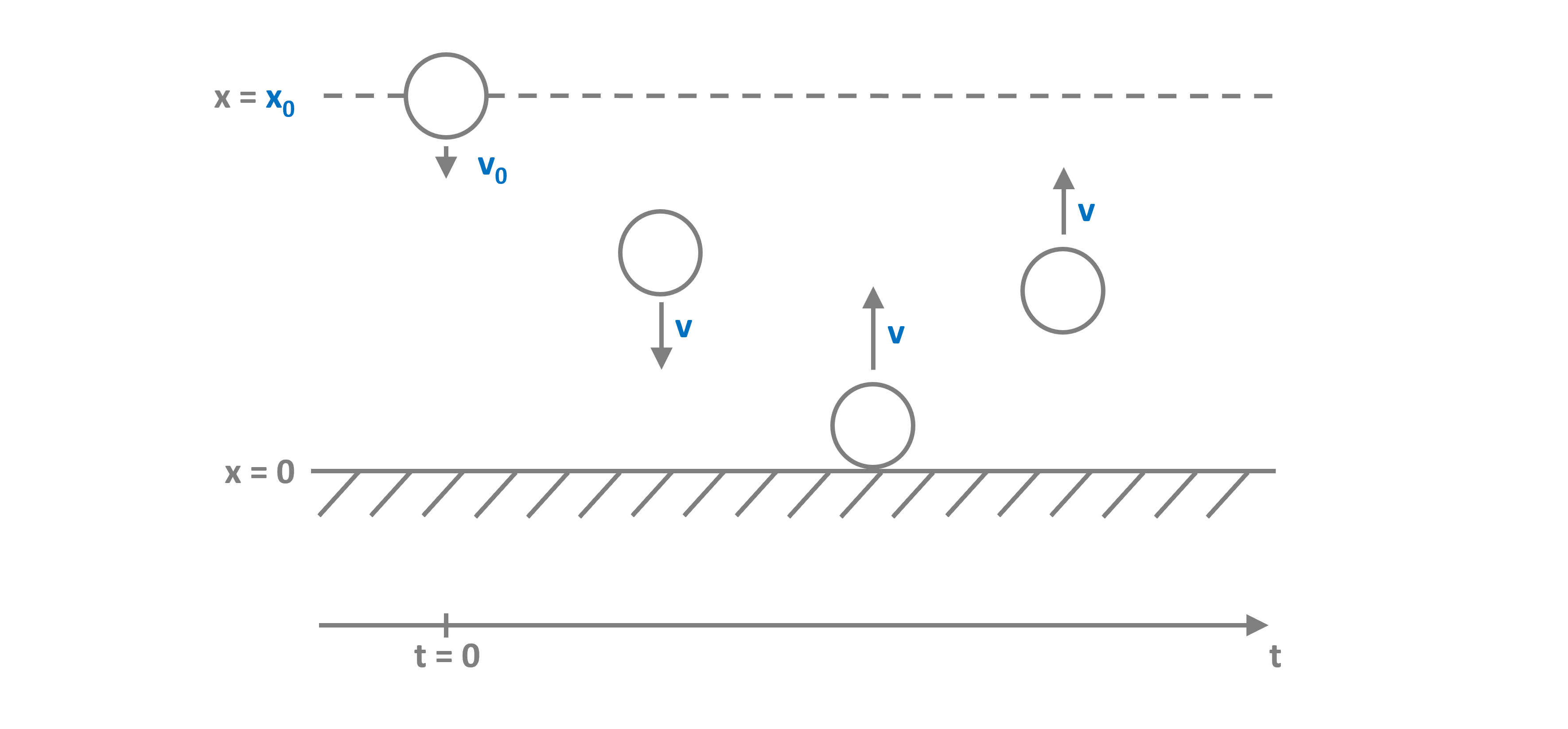

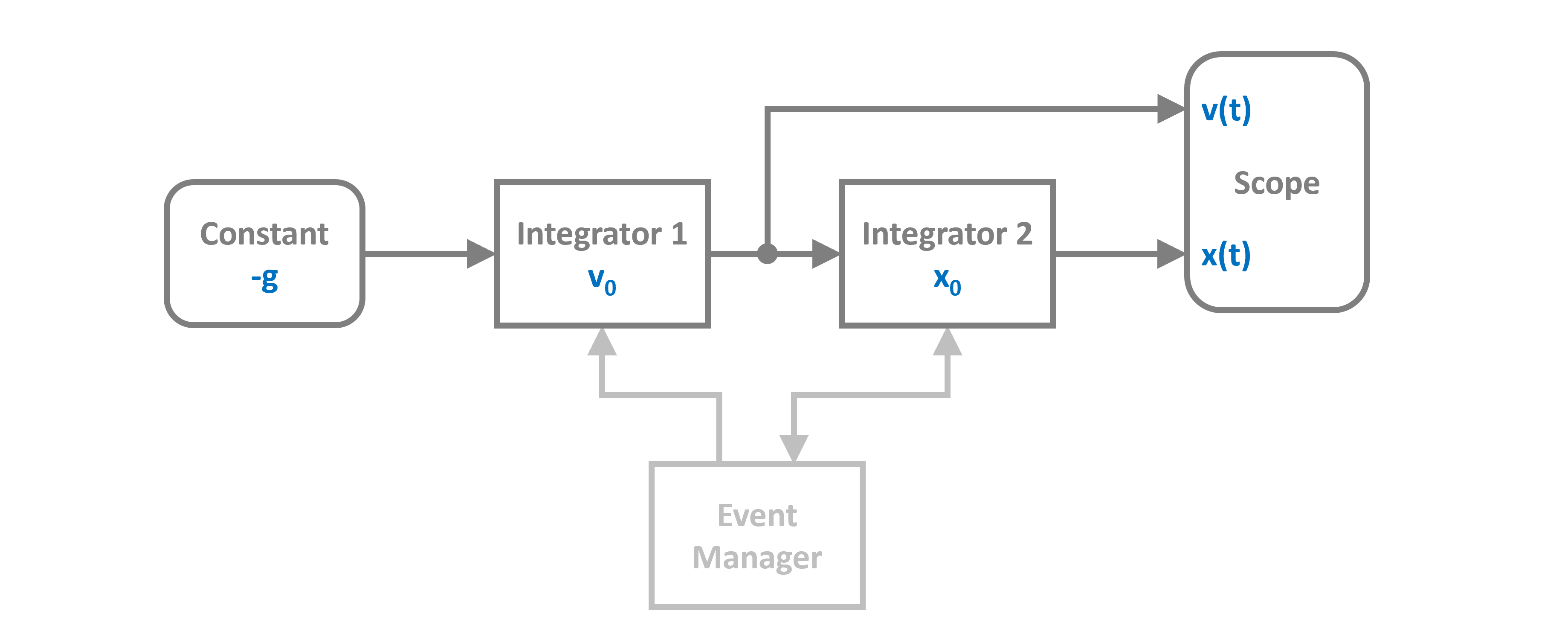

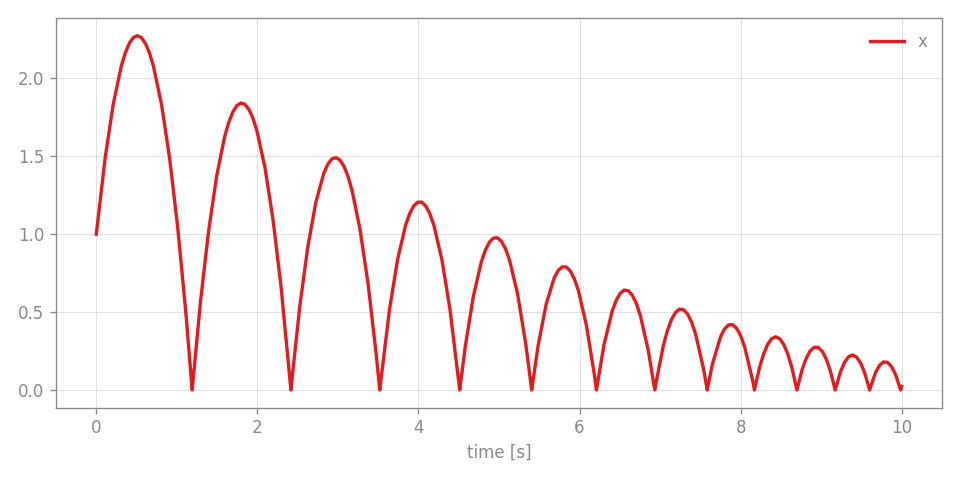

Probably the most popular example for this is the bouncing ball (see figure above) where discrete events occur whenever the ball touches the floor. The event in this case is a zero-crossing.

The dynamics of this system can be translated into a block diagramm in the following way:

And built and simulated with PathSim like this:

from pathsim import Simulation, Connection

from pathsim.blocks import Integrator, Constant, Scope

from pathsim.solvers import RKBS32

#event library

from pathsim.events import ZeroCrossing

#initial values

x0, v0 = 1, 10

#blocks that define the system

Ix = Integrator(x0) # v -> x

Iv = Integrator(v0) # a -> v

Cn = Constant(-9.81) # gravitational acceleration

Sc = Scope(labels=["x", "v"])

blocks = [Ix, Iv, Cn, Sc]

#the connections between the blocks

connections = [

Connection(Cn, Iv),

Connection(Iv, Ix),

Connection(Ix, Sc)

]

#event function for zero crossing detection

def func_evt(t):

i, o, s = Ix() #get block inputs, outputs and states

return s

#action function for state transformation

def func_act(t):

i1, o1, s1 = Ix()

i2, o2, s2 = Iv()

Ix.engine.set(abs(s1))

Iv.engine.set(-0.9*s2)

#event (zero-crossing) -> ball makes contact

E1 = ZeroCrossing(

func_evt=func_evt,

func_act=func_act,

tolerance=1e-4

)

events = [E1]

#initialize simulation with the blocks, connections, timestep

Sim = Simulation(

blocks,

connections,

events,

dt=0.1,

Solver=RKBS32,

dt_max=0.1

)

#run the simulation

Sim.run(20)

#plot the recordings from the scope

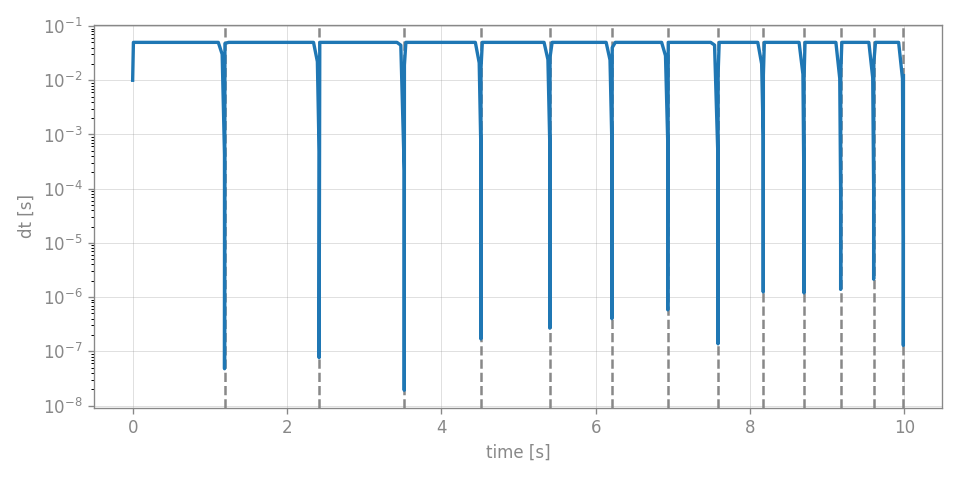

Sc.plot()During the event handling, the simulator approaches the event until the specified tolerance is met. You can see this by analyzing the timesteps taken by the adaptive integrator RKBS32.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,4), tight_layout=True, dpi=120)

time, _ = Sc.read()

#add detected events

for t in E1: ax.axvline(t, ls="--", c="k")

#plot the timesteps

ax.plot(time[:-1], np.diff(time))

ax.set_yscale("log")

ax.set_ylabel("dt [s]")

ax.set_xlabel("time [s]")

ax.grid(True)PathSim is in active development and your feedback is highly appreciated! Dont shy away from filing issues or requests! If you want to contribute in a mayor way, send me a message and we can discuss how!